How Europe’s Aristocrats Invented Class Warfare to Protect Their Privilege

❧

Modern propaganda tells a tidy little story:

Capitalism rose on the backs of exploited workers, and socialism was the righteous response of the oppressed. History tells the opposite: Anti-capitalism did not begin as a cry of the poor. It began as a temper-tantrum of the privileged; nobles who were furious that ordinary workers could finally walk off their estates and earn better wages in the city, or even start from nothing and earn their own fortunes.

When the Industrial Revolution began raising wages for common men and women; far above what the old aristocratic order ever allowed; the nobles panicked.

As Ludwig von Mises observed: “The hatred of capitalism originated not with the masses, not among the workers themselves, but among the landed aristocracy.” — Mises, Economic Policy

Factories threatened the social hierarchy that had existed for centuries:

- No more inherited dominance.

- No more serfs tied to the land.

- No more monopoly on opportunity.

Suddenly, a footman could become a foreman or more, and the “lords” could not stand the competition and humiliation of having a more equal playing field. So the aristocrats launched the first wave of “anti-capitalist” attacks — cloaked, of course, in moral language. They claimed to be defending the workers, while what they actually hated was competition and higher wages.

Higher wages meant fewer servants.

Fewer servants meant less power.

Less power meant the end of aristocracy.

Cue the outrage.

These elites did what elites always do when they feel their entitlement slipping: They invented a story. They dressed up resentment as virtue. They condemned industry not because it harmed workers, but because it liberated them.

Workers fled feudal poverty, elites fled accountability, and so the real class war began; not bottom-up, but top-down; an aristocratic revolt against the economic freedom of the poor.

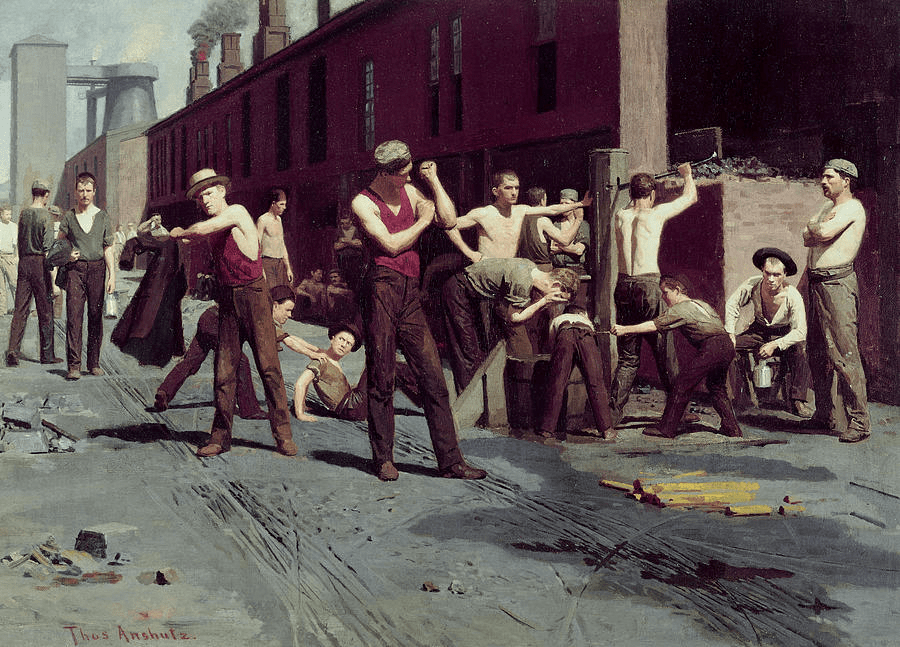

Their rest is earned, not inherited. They build the world others live in. Each scar, each stain, is a mark of dignity — a testament that greatness comes not from titles but from toil.

Communist ideology later seized this resentment, formalized it, and preached it as “justice.” But its root was never solidarity with the laborer. It was fear — the fear of a ruling class watching its inherited power evaporate.

The first anti-capitalists wore crowns, owned vast estates, and dined on fine china.They were not liberators of the working man —they were the reason the working man needed liberation. The historical irony is brutal and undeniable:

Capitalism lifted the poor and the powerful hated it.

❧

The Right Lesson to Remember

When someone rails against capitalism while enjoying privilege, especially when they are comfortably detached from the real burdens of working people — they are part of a very old tradition:

Opposing freedom in the name of the “common good,” while fighting to keep society exactly as it was; beneath them.

Human energy turned outward — to build, to transform, to create something larger than bloodlines. The city rises because men and women choose to rise. Progress is not a gift of the elite; it is the work of the many.

“Class warfare” was not a revolt of the weak; it was a revolt of those who feared the weak might become strong.

❧

Who Benefited — and Who Raged — When Capitalism Arrived?

When capitalism emerged, two groups experienced two very different revolutions:

Workers Gained:

- Higher Wages — Factory pay often doubled or tripled what the fields ever offered

- Mobility — A man could leave the estate and choose his employer

- Dignity — Labor became a skill, not inherited servitude

- Opportunity — The son of a farmer could become an engineer, merchant, or owner

- Independence — No more begging permission from the lord for survival

For the first time in history, the working class had leverage.

Elites Lost:

- Cheap Labor — They had to actually compete for workers

- Control — Workers could walk away, and they hated that

- Status — Their “birthright” superiority looked weak beside new industrial success

- Comfort — A life of servants became costly

- Power — The hierarchy that had propped them up for centuries collapsed

For the first time in history, aristocrats had to earn what they owned. The greatest scandal of capitalism was never poverty — it was the escape from poverty. And the elite class never forgave it for that.

❧

Anti-capitalism, and all its horrifically demented sub-spawns did not rise from the factory floor. They rose from the manor house. The nobles cried injustice only after capitalism began lifting the poor.

The first enemies of freedom were those who feared the common man might rise to meet them eye to eye.

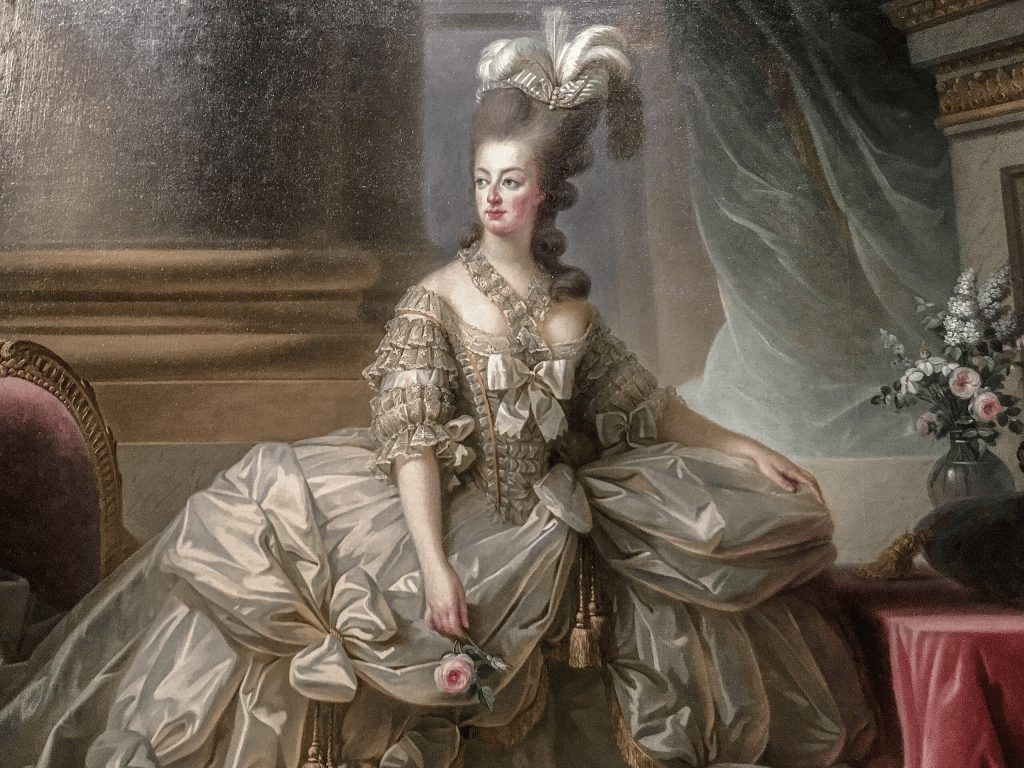

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842)

She stands wrapped in silk and jewels, certain that the world was designed to bow.

Every pearl declares: privilege is permanent — that comfort is a birthright and sacrifice is for others.

But history is not fooled by satin. Virtue cannot be inherited. It must be lived.

When an age forgets that dignity belongs to every soul, not merely to those born in brocade, the very foundations of society begin to tremble. And tremble they did. For while the poor labored and hungered, the court danced, believing that their power would last as long as their gowns were beautiful enough. This portrait captures the final illusion of a dying world: a queen adorned, yet utterly unprepared for justice.

❧

Suggested Reading List

- Ludwig von Mises — Economic Policy: Thoughts for Today and Tomorrow (esp. Lecture 1: Capitalism)

- Deirdre McCloskey — Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can’t Explain the Modern World

- F.A. Hayek — The Road to Serfdom (on aristocratic opposition to free markets)

- Niall Ferguson — Civilization: The West and the Rest (industrial wages and mobility)

- Paul Johnson — Modern Times (rise of socialism and elite ideological origins)